Waiting for my Dad | ©Rose Tibayan

The Reprieve: Reversing Dementia

It was half past noon on a blustery day in Philadelphia. I stood inside the vestibule of the historic Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul waiting for a delayed wedding to begin. Near the basilica’s majestic cast bronze doors, I could see my two sisters and the other bridesmaids adjusting their chiffon gowns while the groomsmen stood along the marble walls in their pressed tuxedos. At their feet, the three-year-old ring bearer had begun to whine. I felt cold. Each time someone opened the door, a gust of wind would blow the tip of my cathedral-length veil a few feet into the air. The belated stragglers would smile and wave, then rush past me toward a waiting attendant, embarrassed that they were late, but relieved to find that the ceremony hadn’t yet begun. I was awaiting the arrival of one person — the man who was supposed to walk me down the aisle — my father.

The Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, Philadelphia, PA | ©Rose Tibayan

After ten more minutes ticked by, the celebrant, Reverend Monsignor John Close, rushed up to me. “We need to start,” he said. I felt panic. It wasn’t right to start without my father but any more delay would further unhinge the clockwork schedule of the day. “Where was he?” My wedding party fell into line. As the first soft notes of Pachelbel Canon in D Minor wafted through the massive stone columns and up into the Corinthian dome ceiling, my guests rose to their feet in their pews and turned their attention to me. As I walked down the 236-foot long cathedral nave holding my mother’s hand, I could feel the eyes focused on me, and I wondered if they were as bewildered as I was that my father wasn’t by my side to give me away. My husband-to be met me at the end of the aisle and, together, we stepped into the marble sanctuary to begin our rites.

Fifteen minutes into the ceremony, my father arrived. His movements created a distraction as he made his way to the front of the church. My eye caught his tall bent frame as he plodded his way past the communion rail onto the sanctuary and toward the choir stalls where the wedding party was seated. My father’s steps were stiff and unsteady. I remember thinking that he walked like a zombie. Instead of the formal black tuxedo that we had selected for him, he was wearing a dark blue suit jacket. It had been a few years since I had seen my father but, on that day, he was so removed from the man I remembered who used to care about the way he looked.

Today, as I reflect back remembering my father’s lumbering walk that day, his messy appearance, and his failure to select the correct jacket, I now know that he was very sick. He had a kind of dementia that is surprisingly common but often missed or misdiagnosed. I know that if a doctor had only recognized the simple signs or symptoms of his illness — all of which were plain to see that day when he walked though the church — his life might have been saved. He may have received a second chance at living life.

NORMAL PRESSURE HYDROCEPHALUS

Most types of dementia are progressive, incurable, and fatal. But there is one kind that is treatable. In fact, the effects of this illness can be reversed with a simple 45-minute long procedure.

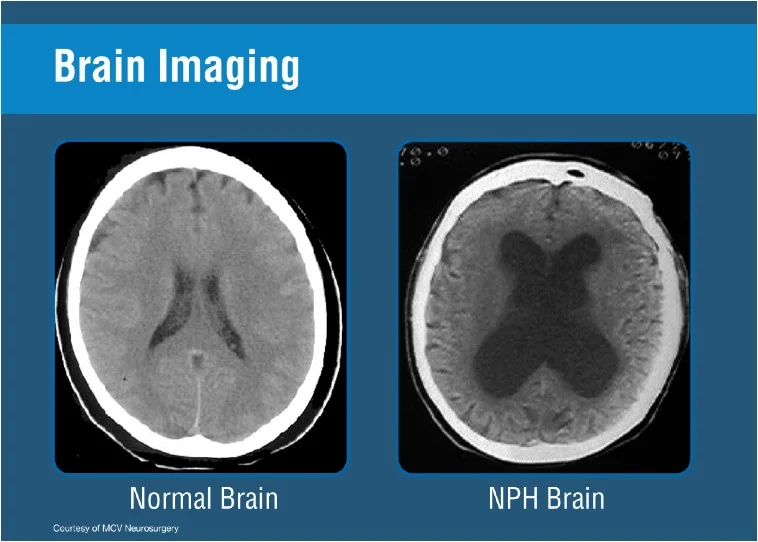

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) -- a long name for an illness that too many know too little about. Simply put, NPH is a syndrome that is characterized by enlargement of the fluid spaces in the brain in association with a triad of clinical symptoms. Many afflicted with NPH are not aware that they have it. Even worse, many of their doctors have never heard of it.

Hydro, of course, is Greek for water. The brain’s water, called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), is produced in the brain, and surrounds the brain and spinal cord, cushioning and protecting it. CSF travels throughout the brain’s four ventricles, refreshing the cortex with nutrients and flushing away any waste. On average, adults produce about one pint of CSF daily. Usually, extra CSF is absorbed by the brain’s surrounding tissues.

Excessive fluid fills the ventricles of the NPH brain | ©Courtesy Dr. Hakim

When that fails to happen, the ventricles become oversaturated and enlarge, resulting in hydrocephalus — otherwise commonly referred to as water on the brain. Ancient Greeks didn’t have a name for the condition but knew of its existence. During the 4th and 6th centuries A.D., Greek physicians Oreibasitos and Aetios wrote about the symptoms and treatment of hydrocephalus.

No one knows what triggers Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) — the form of this condition that affects older people. The adult onset is somewhat of a medical mystery even after all these centuries. We don’t yet know what causes the circulatory path of CSF to be blocked. NPH occurs when CSF builds up in the brain’s ventricles over a lengthy period of time. Because the build-up is gradual, the brain is able to compensate at first for the extra fluid and keep intracranial pressures in the brain nearly normal. At some point, however, the ventricles reach a point of saturation. They enlarge and begin pressing against parts of the brain, pressing it against the skull and stretching nerve endings. Researchers have yet to make a firm connection between symptoms and which portions of the brain are disturbed. The parts of the brain that are most affected are thought to be those located in close proximity to the ventricles within the deeper structures of the brain that control the legs, the bladder, and cognitive mental

processes. As a result, people with NPH end up with three distinct symptoms — gait disturbance, short-term memory loss, and incontinence.

NPH is classified as a dementia, meaning the loss of cognition is beyond what happens during the normal process of aging. Altogether, there are about seventy different types of dementia affecting about 36 million people worldwide. In the U.S., around 7.5 million people have dementia. The Hydrocephalus Association estimates that five percent them — or 375-thousand people, actually have NPH.

Unlike most of the other forms of dementia, NPH is not a neurodegenerative disease. But, because its triad of symptoms are often associated with the normal characteristics of aging, many people with NPH remain undiagnosed or incorrectly diagnosed with other forms of dementia such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, where brain matter shrinks as cells die. NPH, however, is a case of the brain’s fluid mechanics gone awry. Brain cells are not lost but simply compressed. This is why it is relatively simple to treat and cure. And even though most doctors don’t know about NPH, the disease was discovered more than half a century ago, and so was the cure.

San Juan de Dios hospital in 2011. Bogota, Colombia | ©Rose Tibayan

A BOY IN BOGOTA

It was December 1957, and San Juan de Dios Hospital was in a flurry. A 16-year-old boy had just been brought in. He had been playing in the street and was hit by a car. The boy arrived pale, confused, and gasping for breath. On the side of his head was a hematoma — a giant pocket of blood under the skin. To ease the pressure, doctors cut a small hole in his skull. He remained unresponsive in a cloudy haze and was diagnosed with irreversible brain damage. After two weeks doctors sent him home.

A month later the boy’s father brought him back. The boy’s condition had not improved. He was now incontinent. He was almost always drowsy, or asleep, and often needed to be slapped awake so that he could eat. A neurologist named Salomon Hakim was on duty that day. Neurologists are medical specialists who deal with disorders of the nervous system. Hakim had an x-ray taken of the boy’s head and saw that the ventricles were enlarged. He removed 15ml of fluid from his brain for some tests. What happened the next day was nothing short of a miracle. After more than a month in a near-comatose state, the boy began talking. A few days later he lapsed back into unresponsiveness and, once more, Hakim removed fluid from the boy’s brain. Hakim also implanted a shunt to allow for the continued draining of fluid. One day after that operation, the boy began talking. Five days later he was no longer incontinent and eating on his own. Within three months, the boy’s speech returned to normal and he was back in school.

Hakim had a hunch about the boy’s incredible recovery. As he later wrote in his case report, “One of the residents had stated that he could not see the reason for the improvement in the patient after the removal of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the lowering of the CSF pressure since his pressure had been normal. This was the moment when we thought that a possible explanation could be based on the relation between the CSF pressure and the area on which it is exerted.” Hakim wondered if the same routine would work with another patient. It wasn’t long before another case would present itself.

On February 12, 1958, a 52-year-old man was brought to the hospital by his wife. He was a professional trombone player. For the past year he had been unable to play his instrument as well as he used to. His legs were stiff, his balance unsteady, he had trouble turning, and was unable to climb stairs. The man tired easily, was apathetic, and careless in his appearance. “What is wrong with you?” Hakim asked him. “I can’t walk, my legs don’t obey me,” he replied.

Gait disturbance is the first of the triad of symptoms to appear in all classic cases of NPH. Some feel as if their feet are glued to the floor and then walk with a shuffle. The second NPH symptom, short-term memory loss, soon follows. The man’s wife told doctors that her husband’s mental state had changed. He was slow in thought, spoke slowly, was easily confused, unfocused and very forgetful. The third NPH symptom is incontinence or urinary urgency. The man looked untidy as his pants were often soiled from dribbling urine. His wife said that he did nothing but sit and just exist most of the time, and wasn’t interested or worried about anything. X-ray images of his brain

showed enlarged ventricles.

Over the next few weeks, doctors drained CSF from the man’s spine and his symptoms improved. Six weeks after he first arrived at the hospital, surgeons implanted a shunt to allow for continued draining of fluid. The next day he had remarkably improved. Three days later he was even more alert and responsive and could stand on his own. Soon he was feeding himself and walking with a cane without any assistance. His neurological and mental states continued to improve. He became coherent, well oriented, and was able to return home. “Many patients without the hope [of a cure] can be rescued from their dementia through a ventricular drainage if they, indeed, have this kind of hydrocephaly,” wrote Hakim about his discovery. “In this way we can propose the birth of a new chapter in neurosurgery — that of treatable dementias.”

Salomon Hakim had discovered a dementia that can be reversed. That makes it remarkable and important for doctors to know about it. “Truly reversible dementias are hard to find outside of NPH,” says Norman Relkin, a neurologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, “which is what makes NPH so special.”

Doctors before Hakim had encountered the phenomenon of NPH but hadn’t pursued it further. Cases of patients with gait disorders and cognitive decline had been reported by L’Hermitte and Mouzon (1942); Roger, Paillas, and Tamet (1950); LaFon, Gros, Enjalbert (1950); and Foltz and Ward (1956). In the latter case, the doctors had drained CSF from the ventricles with successful results. However they had chalked it up as an anomaly without further elaboration.

It took a special doctor — one with mechanical inclinations and intrinsic curiosity, who questioned things that others were simply content to accept, to take NPH out of autopsy labs and relative obscurity into the real world as a clinically diagnosable disease. Hakim was remarkable, but there was something in his circumstances and the way his career unfolded that would conspire to keep the disease he discovered obscure for decades in spite of all his brilliant work.

THE ENGINEER DOCTOR

Salomon Hakim was born in 1922 in the port town of Barranquilla, Colombia. His parents, Sofia Dow and Jorge Hakim, had emigrated from Lebanon the previous year by way of Cuba, where Sofia’s father owned sugar plantations. The young Hakim was a happy and curious child who liked to see how things worked. His father encouraged this curiosity by giving him access to tools and parts so that he could build things.

“I never played with tops, cars or bicycles,” he would later tell a family friend. “I played with wires, batteries and light bulbs. Oh, how I enjoyed those!” Hakim’s father would create mini flamethrowers by squeezing the zest of a citrus peel toward a lit match to create a burst of flame. It was magic to the young Hakim. To his father it was an opportunity to interest his son in chemistry as he explained the flammable combination of chemicals found in the skins of tangerines, lemons, and oranges. The family would later move to the town of Ibague, where Hakim’s father owned a fabric shop called El Buen Gusto.

At the age of 11, Hakim left for Bogota to study at a parochial school called El San Bartolome. There, his science teacher, a physician and Jesuit priest named Celestino Redin, steered him toward physics. Hakim built a radio that allowed him to bridge the geographical distance that he felt with being so far away from his family. He used his invention to talk to his father every day. “He was tremendously respectful and caring of his family,” Redin later recounted in a book about Hakim’s life. “He had a striking tenacity and such commitment to his studies — of a kind I have not seen in many other young men.” Hakim wanted to become a doctor. He went on to study medicine at La Universidad Nacional where he specialized in neurology.

Hakim graduated from medical school in 1948, around the time the Colombian government was examining the state of its medical schools. Results were dismal. Medical education in Colombia lagged behind the U.S. and Europe by 50 years. That year Hakim traveled to New York City in search of a way to further his medical education. He met Gilbert Horrax, head of the Neurosurgery Department at Lahey Clinic in Boston, Massachusetts, who agreed to take Hakim under his wing if he improved his English.

In 1950, Hakim and Yvette Daccach were married. Yvette’s parents, like Hakim’s, had emigrated from Lebanon. The couple shared a passion for music and art, and soon after their wedding they moved to the United States. “While my parents were living in Boston my older sister, Marie Claire, and I, were born,” Hakim’s eldest son, Carlos, told me. One of Hakim’s mentors at the clinic was James Poppen, the first neurosurgeon to operate on the lower back of John F. Kennedy while he was in the Navy. Mentor and student bonded and began a lifelong friendship. When his fellowship at Lahey Clinic ended Hakim returned home to Bogota but returned to Boston in 1954.

Hakim took classes at Harvard and thrived in the intellectual atmosphere. He and Yvette lived on Marlborough Street, about a mile away from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) where he had a research internship. Later, they moved farther away from the hospital to St. Paul Street where they settled comfortably into the surrounding community. “He enjoyed Boston very much,” Carlos told me, “except for the winters which he really had to get used to.” Cold temperatures in the lab were also something that Hakim needed to get used to. For the next seven years he worked as a research fellow in neuropathology at MGH where he donned a lab coat each day and stepped into a frigid lab to perform autopsies on cases with Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Hakim saw many cases of enlarged ventricles with loss of brain matter. Once in a while he would stumble upon a case of enlarged ventricles without loss of brain matter. The latter was clearly a sign of NPH, but Hakim didn’t know it at the time. As he continued to find more of these cases Hakim tried to make sense of what he saw.

On March 10, 1964, Hakim published his first essay about NPH in Spanish, “Some Observations on C.S.F. Pressure. Hydrocephalic Syndrome in Adults with ‘Normal’ C.S.F. Pressure — Recognition of a new Syndrome.” Hakim drew upon a theory of hydrostatics by Blaise Pascal, the seventeenth century French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher, to explain the mechanics behind NPH. “We believe that the brain impairment in hydrocephalus with normal C.S.F. pressure can be explained by Pascal’s Law,” wrote Hakim. “First stated 300 years ago, this law says that: When a pressure is

applied on a certain area of a confined liquid, the pressure is transmitted without gain or loss to each similar area within the vessel.” Hakim used a series of photographs of balloons, arteriograms of actual cases, and diagrams illustrating the application to NPH of Pascal’s Law by showing cross sections of brains of similar pressures with different sized ventricles. He described the details of his first live cases — that of the boy on a bicycle and the trombone player. Implanting shunts in those patients had given them back their lives. Hakim felt, however, that a shunt shouldn’t be one-size-fits-all.

Salomon Hakim in his lab | ©Courtesy Dr. Hakim

Back in his lab in Colombia he worked on developing an adjustable valve for the treatment of NPH. A shunt is a device consisting of a valve and two thin, flexible tubes. Together, they work to drain CSF from the brain’s enlarged ventricles. As the pressure in the ventricle increases, a one-way valve in the shunt opens, and excess CSF drains from the brain into the abdominal cavity or the atrium of the heart. “When my father discovered NPH he started working on the shunt almost at the same time,” Fernando, Hakim’s son, told me. “Other shunts during that time were just a tube with a small slit that would control the pressure.” Fernando was referring to the slit valve, a simple device developed in 1949 by surgeons Frank Nulsen and Eugene Spitz. The Spitz valve regulated CSF flow. However, it did not monitor pressure, was constructed with polythene tubing, and often failed. Clotting and infections were the leading causes of shunt failure. Salomon Hakim wanted to control pressures inside the brain without having to do repeat surgeries. He spent his extra hours tinkering in his second-floor home laboratory trying to create a shunt valve that could be adjusted.

In his home lab Hakim was highly organized, often worked on several projects at a time, and kept notes in separate briefcases and folders. He preferred to work in absolute silence or to his favorite composer, Beethoven, at a low volume. From his upstairs window Hakim could look out into the yard and watch his four young children at play. Often he would bring them upstairs into the lab and, as his own father had done with him, let them tinker with tools and gadgets. “My father taught us how to use all those devices, all those machines. He showed us the physics of everything,” Fernando told me. “Why a car accelerates, why this happens, why that, whatever. At what temperature does water boil? He would put a thermometer in the water and show us.” When friends stopped by Hakim would come downstairs and join them for Yvette’s almond cakes and coffee. Hakim’s prized collection was a set of precision tools used for tweaking watches. With those tools he shaved rubies under a microscope. He wanted to carve a gemstone that would act as a stopgap in the valve that he had in mind. His labors resulted in the Hakim Valve, which had a stainless steel

cone, a ruby ball, and a spring-loaded pressure control. The prototype had one pressure setting. Eventually, he created a valve with three pressure settings — low at 35mm, medium at 65mm, and high with pressures over 90mm. Springs of different thicknesses allowed the variations in pressure. As a result of this programmable ball technology, the Hakim shunt is one of the most widely-used shunts worldwide today.

BUILDING AWARENESS OF NPH

Hakim had established his theory of NPH, created a technology to treat it, and had restored the quality of life of numerous patients. Now, he wanted to spread the word so that other doctors could become familiar with the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. His efforts had been lauded in his home country of Colombia but he wanted to spread knowledge about NPH to the U.S. He reached out to one of his former mentors in Boston, Raymond Adams, who was now Chief of Neurology at MGH. Hakim told Adams about his discovery. Instead of supporting his former student, however, Adams apparently told Hakim that there was nothing new about the information he was offering. “Everything has already been published,” Adams, said, according to a July 2010 article in the New England Journal of Medicine by Columbia University doctor, Matthew Wallenstein. “Perhaps you don’t have good libraries in Colombia.”

“My feeling is that my father did not think that Dr. Adams understood his interpretation of the cause of NPH,” says Carlos. “Dr. Adams gave a different analysis of what he thought the cause of NPH was which really did not have much scientific support. Dr. Adams understood the clinical aspects and implications of NPH, but did not understand the physics of it.”

Despite Adams’ rejection, Hakim continued with his work. In 1965 the wife of an important doctor in Bogota was reported to be acting ‘crazy.’ Hakim examined the patient, determined that she had NPH, and offered to perform the surgery. Her husband refused, telling Hakim that if his wife needed surgery, it had to be done in the United States. Hakim offered to accompany the patient to the U.S. because he told the husband that American doctors were unfamiliar with NPH. Hakim accompanied the woman and her husband to MGH in Boston, where he presented the woman’s case and revealed his discovery about NPH. After the woman’s successful shunt surgery, Hakim began collaborating on a paper about NPH with Adams and other MGH neurosurgeons.

On July 15, 1965 the New England Journal of Medicine published “Symptomatic Occult Hydrocephalus with Normal Cerebrospinal-Fluid Pressure — A Treatable Syndrome.” The authors of the paper were listed in order as: R.D. Adams, C.M. Fisher, S. Hakim, R.G. Ojemann, and W.H. Sweet. The paper presented three cases. First came the case of a 63-year-old woman who, in October 1958, complained of “uncertainty of gait, inability to think clearly, and incontinence of urine.” Then there was a 66-year-old woman who, in May 1961, began to suffer “impaired memory and ataxia of gait.” The third was a 66-year-old pediatrician with a six-month history of “increasing slowness of thought, unsteadiness of gait, and incontinence.” The article included descriptions of the symptoms, clinical and medical histories, and an interpretation of NPH using Hakim’s theories. In all cases there was a dramatic recovery of mental and motor functions following the drainage of CSF.

The five authors listed in the article were affiliated with MGH — perhaps the most prestigious neurosurgery center in the U.S. at that time. Hakim had been a clinical resident and researcher at the center in the 1950s. Who were the others? Adams, who met Hakim in Bogota and later became one of his mentors, was Chief of Neurology. Fisher was a colleague with whom Hakim had done work using advanced microscopy to develop a technique measuring tiny blood vessels in the brain. Ojemann was a resident in the Department of Neurology, and Sweet was the Chief of Neurological Service at MGH.

Of the six cases published first in all of the medical literature about NPH, five came from Colombia — all patients of Hakim’s. The sixth was the woman that Hakim had accompanied from Colombia to MGH in Boston. The groundwork, the theory of NPH, and the cases, clearly had all originated from Hakim. Yet, when the New England Journal of Medicine article was published in 1965, Hakim was listed as the third author. After the article came out, Hakim asked Adams why his name had appeared third in the order of authors. Adams told him that, in the United States, it was standard practice to list authors in alphabetical order.

Adams on the left; Hakim is on the right | ©Courtesy Dr. Hakim

An examination of the manuscript submission guide on page 164 of the New England Journal of Medicine Vol. 273 (1964), in which the article appears, reveals nothing about the order in which authors should be listed. Rules of order when listing multiple authors vary with each scientific field. So much so that, today, the New England Journal of Medicine author guidelines encourage authors to decide, amongst themselves, the order in which their names will appear. “Such matters need to be adjudicated locally, with the corresponding author making the final decisions about authorship.” Some fields list authors depending on their degree of involvement in the work. Those who contributed the most are listed first. An abstract in Nature magazine (June 1977), called “Games People Play with Authors’ Names,” reveals why an alphabetical order of listing, despite its seeming fairness, is not truly equitable.

“Alphabetical ordering reduces scope for debates about credit, but not recognition: one cannot escape the fact that K. Aa, the scientist whose name happens to appear first… has a particular advantage in this respect.” Adams received a large share of credit for the work that Hakim had done. This was no more evident in a September 1970 article published about NPH in the New England Journal of Medicine called, “Diagnosis of Normal-Pressure Hydrocephalus” by Benson, LeMay, Patten, and Rebens which in the first sentence begins, “In 1965, Adams et al. reported…”

Hakim’s supporters conceded that, although he had great prestige in Colombia, an American publication such as the New England Journal of Medicine probably would not have published the article with Hakim as sole author. In a Spanish book about Hakim’s work titled, “From Hakim's Valve to the New Theory of Cranial Mechanics,” author German Cubillos Alonso says that the most valuable contribution made by the doctors from MGH was in lending the prestige of their names to the paper — particularly Adams and Fisher who, at the time, were two of the most well-known figures in neurology.

The New England Journal of Medicine article did give great momentum to Hakim’s work. He traveled abroad to give lectures. He published papers about NPH in 1966 and 1969, then two more in 1971. In 1967 the Spanish edition of Life magazine featured Hakim in an article titled, “The Miracle of a Colombian Neurologist.” In 1969 Hakim received special mention in the Science Prize from the Alejandro Angel Escobar Foundation. In 1970, Colencias — a government institute in Colombia created to support scientific research, awarded him the National Science Award. In 1974 and 1976 he received the Science Prize from the Escobar Foundation. Hakim was collecting many accolades but most were given by organizations in his own country. Ten years after the publication of that much-acclaimed New England Journal of Medicine article, Hakim remained alone in promoting NPH.

Fortunately for Hakim, his children chose to follow in his footsteps. Three of his four children — Carlos, Rodolfo, and Fernando — all became involved in the research, diagnosis, and treatment of NPH. Today Rodolfo and Fernando are medical doctors of neurology. Carlos, his eldest son, would be the one to take his father’s work to the next level.

THE PROGRAMMABLE SHUNT

By now Hakim was established at the University de los Andes in Colombia where he began to expand his research into engineering. He helped to set up a research lab which pioneered projects combining biological sciences and engineering. He established a program to study the biology of the cranial cavity, hydrocephalus, and normal pressure. The lab enabled him to receive valuable academic feedback from students and colleagues. In 1976 Hakim’s group published a study on the theory behind cranial mechanisms and its relation to NPH. Carlos was enrolled in the

university as a mechanical engineering student. In his thesis, he wrote about a control mechanism called the "hydraulic amplifier" used to detect intracranial pressure. It was this work that laid the foundation for the creation of a new innovation — the programmable valve.

As his father had previously done, Carlos headed to Boston. There he pursued a joint PhD in biochemical engineering at MIT and Harvard. It was there that he perfected the programmable ball technology that his father had developed by shaving rubies in his home lab a decade earlier. The Hakim programmable valve can be adjusted to avoid over or under drainage with 18 pressure settings in 10-mm increments. “Without a programmable shunt you would see the patient improve for a while and then deteriorate again and people really didn’t understand what was happening,” says Carlos. “With a programmable shunt you can do the fine-tuning of the pressure. What used to happen before, was if you had normal pressure, the doctor would have to implant a shunt with a lower than normal pressure for the ventricles to reduce in size. But once they reduce in size you have to increase the pressure a little bit. Otherwise they continue to reduce in size and the patient deteriorates again.”

Today, Codman, a Johnson & Johnson company, manufactures the Hakim Programmable Valve. Government approval of the valve in the U.S. ten years ago has reawakened public interest in NPH. Compared to other forms of medical treatment, the cost is fairly reasonable. A shunt operation, or craniotomy, costs about $20,000. A shunt device, depending on which of the four approved devices is selected, can cost between $2,000-$6,000. Imaging and post-operative costs range between $5,000-$10,000. Medicare and insurance cover the craniotomy procedure, but reimbursements for the shunt and follow-up care are increasingly diminishing. “The Hakim shunt has the programmable ball,” says Norman Relkin of Weill Cornell Medical College. “The ball, which is very clever technology, is probably the most widely used and, at least in the centers I’m aware of in this country, the Hakim programmable shunt is the most widely used.”

The effectiveness of the Hakim shunt even reached the Communist world. It was 1980 and Solomon Hakim received an invitation from Moscow. The Olympic Games were scheduled to be in the Soviet Union that year. Leonid Brezhnev, the republic’s 74-year-old leader, was supposedly in ill health. There were rumors that Brezhnev was suffering from dementia. Political cartoonists, worldwide, took advantage of this opportunity to poke fun at the aging leader, whom they cruelly depicted in jokes as dumb-witted and suffering from dementia: At the 1980 Olympics, Brezhnev begins his speech “O!” — applause. "O!" — more applause. "O!" — yet more applause. "O!" — an ovation. "O!!!" — the whole audience stands up and applauds. An aide comes running to the podium and whispers, "Leonid Ilyich, that's the Olympic rings, you don't need to read it!"

While receiving the Star of Lenin, Brezhnev reportedly fumbled his words and shook as he walked. The story of how Hakim may have been involved in helping restore Brezhnev back to health is recounted in a book prologue by a Hakim family friend named Efraim Otero-Ruiz. As Ruiz tells it, Hakim was asked to bring several of his programmable valves to a show-and-tell in Zagreb, Yugoslavia. There, he was asked to leave the valves as a gesture of goodwill, which Hakim did. Then, in Moscow, Hakim was invited to examine several patients with cerebral problems to determine if they

were suffering from NPH. Brezhnev then apparently disappeared for about a month, and returned to the limelight a completely different man with his faculties intact. The Russian press said that he had a vascular cerebral problem caused by his diabetes, but made a quick recovery thanks to Soviet scientists. Hakim, apparently, never saw Brezhnev but wondered if the Soviet leader’s x-rays had been among the anonymous films he was asked to examine. Given the newspaper articles that Hakim read during this time, Ruiz says that Hakim was convinced Brezhnev had suffered early symptoms of NPH and had been treated with one of the valves that Hakim had left in Yugoslavia.

HELPING THE ELDERLY

Hakim often expressed deep compassion for those elderly with undiscovered cases of NPH saying, “These patients are the most important and surprising because of the danger that they will be misdiagnosed and placed in a hopeless category [of] organic brain disease. It is in the large group of patients with late-life dementia that further cases must be sought.”

My father was one of those cases.

Five years after my wedding, my mother died. My father, who was now eighty years old, was left alone. After researching and touring some local nursing homes, my two sisters and I decided that a nursing home was out of the question. Unlike my sisters, I had no children, so my husband and I took my father to live with us. We moved him from the home in Delaware that he had shared with my mother for 40 years to our condo in downtown Chicago. In the years before her death, my mother had taken my father to a variety of doctors — none of whom could figure out exactly what was ailing him. Many assumed that it was likely Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. My father was the victim of an old-school method of diagnosing Alzheimer’s — a diagnosis of exclusion.

I talked about this recently with Dr. Relkin, at Weill Cornell Medical Center. “In those days,” he said, “you were told you rule out everything else and if there’s nothing else that’s causing it, it’s probably going to be Alzheimer’s — but you won’t know until the person dies.”

My father had been lumped in with patients whose minds were hopelessly lost. Not one of his doctors ever recognized the telltale triad of NPH symptoms, even though they had, by now, become more pronounced. He had great difficulty walking, asked the same questions repeatedly, and would go about with urine-soiled pants. To my mother’s astonishment, he didn’t care about how he looked. Friends couldn’t understand what was happening to him and, because they didn’t know how to help him, stayed away. Given his gregarious personality, those must have been difficult years for my father. Eventually, he settled upon a daily routine at their home where he would sit in front of the television for hours, eat a few snacks, then retreat into his bedroom and plant himself in a favorite urine-soaked green armchair and stare at the walls.

For years, my husband and had I enjoyed the freedom that came with a lifestyle without the responsibilities of rearing a child. That all changed with the arrival of my father. In Chicago, I took my father to my internist, Julie Brandeis, for a physical examination. After the checkup, he got up and made his way over to the chair where his clothes were folded. Brandeis noticed his gait. “Does he always walk like that?” she asked. I said yes. She instructed him to make a complete turn while standing in the same spot. It took my father about a dozen steps to make that complete turn. Brandeis looked at me and said, “He needs to see a neurologist.”

IT LOOKS LIKE PARKINSON'S OR ALZHEIMER'S, BUT IT'S NOT

What was happening to my father was exactly what Hakim had worked all of his life to prevent. But the correct diagnosis of NPH is often missed to this day, even with patients who have access to the best doctors in the world.

Harold Conn was prepared to get older. He had read, seen, and heard of just about every disease that could affect him in old age. He was a doctor, after all, a hepatologist who had spent decades teaching about liver diseases and clinical surgery at Yale. It was 1993 and Harold was looking forward to retiring. He and his wife, Marilyn, had just moved into a spacious eleventh floor waterfront condo in Lauderdale by the Sea, Florida — a breezy town nestled between the Atlantic Ocean and the Intercoastal Waterway.

Not long after the move, Harold began to have trouble walking. Strolls along the beach became a ponderous effort. He described himself as “lurching” from one spot to the next, staggering and swaying with each step. Other elderly people limped or walked slowly but when Harold walked his feet seemed stuck to the floor. He looked as if he were crossing a large steel sheet wearing shoes with soles made of magnets.

Harold Conn as a college student | ©Courtesy Harold Conn

“The first thing I noticed was that my legs were clumsy,” he says now. “I could not put my feet exactly where I would like so that my walking was a little irregular. Another physician saw it. He had been walking behind me and he thought he saw something different.”

The colleague suggested that Harold see a neurologist. But, as one doctor might tend to do with the unsolicited advice of another, he ignored it. Two years passed as his walk grew progressively worse. When Harold finally admitted that he needed help, he turned to familiar territory to find the best care that he knew — to the Department of Neurology at Yale School of Medicine.

“I was on the faculty at Yale,” says Harold. “So I picked the best neurologist, or the one I thought was the best.”

One of the tools neurologists use to diagnose patients is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) — a medical imaging technique that shows internal structures in detail. Harold’s MRI brain scan showed that he had dilated ventricles and sulci — meaning that the cavities and fissures in his brain were bigger than they should have been. Because of

this, his cerebral cortex — the “meaty” parts of his brain — were getting pressed up against the edges of his skull resulting in symptoms. The senior neurologist at Yale diagnosed Harold with a Parkinson’s disease-like syndrome caused by cerebral atrophy — a shrinking of the brain caused by the loss of brain cells. Unhappy with what he heard, Harold sought second, third, and fourth opinions. Three other senior neurologists confirmed the initial diagnosis.

In the years that followed, two other symptoms appeared. Harold began to soil his pants. And, more and more often, he couldn’t recall things that had just happened. He now had the classic triad of symptoms — the magnetic gait, incontinence, and short-term memory loss that Hakim had identified as the key telltale markers of NPH. And yet, none of his doctors told him that there was a way out of his misery.

During a follow-up at Yale five years after the initial diagnosis, Harold was told that he would eventually lose his mind. Marilyn, who had kept a daily diary of their lives since their marriage in 1944, noted that her husband was no longer funny. His quick, sharp wit was slowly disappearing. Now, at 77 years of age, Harold tried to maintain his day to-day life. He tried to keep up with a job he held as a consultant at a nearby university and spend time with friends. But his condition was defeating him.

“I quit playing squash and bridge, my joie de vivre was disappearing, and my gait was rapidly deteriorating,“ said Harold. “I could barely walk to the garage from my office at the University of Miami.”

Marilyn and Harold Conn in their Florida condominium | ©Rose Tibayan

Despairing at being told that there was no known effective therapy for his condition, Harold and Marilyn cancelled their plans for their 50th wedding anniversary and began the task of putting their affairs in order.

“I quit my job at the university,” Harold said, “and started to accumulate sedatives and analgesics in the hope that I could dispatch myself to a better world.”

In the spring of 2003, even with the aid of a walker, Harold could now barely walk. He wrote to his neurologist in New Haven for help in getting a scooter. To this day, he doesn’t know why, but his request was refused. As terrible as that act of refusal was, Harold says, it started a series of events that eventually brought him out of his misery.

He turned to a new neurologist for help. That doctor examined Harold and told him that he did not have Parkinson’s disease. Instead, he had a condition called NPH. Harold had never heard of it. He was even more stunned to hear that the terrible symptoms he had been living with for the past decade could be made to disappear with a relatively simple procedure called a shunt implant. The neurologist referred Harold to a local neurosurgeon named Linda Sternau. Sternau was the director of Neurological Services at Mt. Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach. Harold went to see her and was told that a lumbar puncture, which could be done right then and there, would determine if he was a good candidate for a shunt. Sternau sterilized, put on a gown, and arranged Harold on the table with sterile drapes.

“I was there,” Marilyn Conn recalled. “Harold got up on the table with great difficulty.”

A lumbar puncture, also called a simple spinal tap, is a test that a neurologist will perform on a shunt candidate to confirm if the patient truly has NPH. The procedure, usually done in the doctor’s office, often ends with dramatic results. Those who witness it are sometimes dumbfounded. Patients who arrive in wheelchairs and walkers, barely able to speak, later walk out of the doctor’s office on their own two legs and begin chatting. Sternau removed 60 ml, or about two ounces, of cerebrospinal fluid from Harold’s spine.

“And as the fluid, then, proceeded to drip out of the catheter of the needle I could sense a change in my mental state,” said Harold. “As each drop came out it seemed that I became more attentive, more alert, more responsive. At the end of the procedure, they removed the needle and I slid off the table and walked around the room virtually normal. I hadn’t walked in six months.”

Sternau scheduled to have a permanent shunt implanted in Harold’s brain a week from that day. “I was a dead man,” Harold said, “who had been given a reprieve.”

MY TRIP TO BOGOTA

It’s a six-hour flight from Newark International Airport to Aeropuerto El Dorado Bogota. I had arranged this trip to Colombia to meet the doctor who had discovered Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, and how to treat it.

Bogota’s strong morning sun had burned off the clouds by the time I finished eating breakfast. The capital city is one of the largest in South America: nearly nine million people live in Bogota and its suburbs. It’s a polluted city rising 8,612 feet above sea level and, at times, I found it difficult to breathe. The best way to avoid a headache was to move about slowly. I had set aside the day after my arrival to visit Salomon Hakim’s old stomping grounds — San Juan de Dios Hospital where, more than 50 years ago, he encountered his first live cases of NPH in the 16-year-old boy who had been hit by a car and the 52-year-old trombone player who could no longer play his instrument.

Doctors are highly revered professionals in any part of the world, but especially so in Colombia. In fact, if you are an educated, respectable person in Colombia, you may be called “doctor” or “doctora” as a sign of respect, even though you don’t hold a PhD or medical degree. I was pleased to find that the person who would be taking me around town and translating for me, Catalina Ceballos, was actually a newly graduated medical doctor.

We follow a police officer weaving through Bogota traffic on his motorcycle | ©Rose Tibayan

My hotel was only four miles away from the hospital but that meant a 20-minute ride through Bogota traffic. Catalina expertly maneuvered her small car through clots of sherbet-colored buses and daredevil motorbike commuters. Road construction lined the major arteries as far as the eye could see. Upon arriving in the center of Bogota we passed blocks of retail stores, a large swath of public grounds called Millennium Park, and arrived at an area informally known as the hospital center where several hospitals were clustered just blocks from one another. I saw that San Juan de Dios Hospital occupied the most amount of space among all of the hospitals.

Founded in 1723, it had been built centuries ago when land was plentiful and the city wasn’t as densely populated. Today, its buildings sit crumbling inside a gated oasis of grass-covered property dotted with large shady trees. Homes of Bogota’s working class surround the hospital compound and unemployed young men loiter on the corner. Catalina tells me it’s not safe to take my camera out of my bag because it might attract too much unwanted attention on the street.

Salomon Hakim worked at San Juan de Dios hospital during its peak, when it was considered the best hospital in Colombia. Later, it housed the famous Instituto Nacional de Inmunología (National Institute of Immunology) where Manuel Elkin Patarroyo, a Colombian pathologist, carried out work on a synthetic vaccine for malaria. The hospital’s emergency room entrance was still clearly marked. I wondered if the entrance was the same one where, half a century ago, Hakim’s first NPH patient — the 16-year-old boy — had been rushed through on that December day. I cautiously looked over my shoulder, took my camera out of my bag and began snapping pictures. After a few minutes, Catalina and I returned to her car and headed out of downtown Bogota. The Hakims lived seven miles away to the north and we were expected in an hour.

MEETING SALOMON HAKIM

The Hakim family lived in the northern section of Bogota at the base of the lush hills of Monserrat and Guadalupe. The high-rise dwellings in the neighborhood overlooked the Seminario Mayor de San José — a landmark Catholic seminary built in 1581. Nearby, well-dressed professionals lunched al fresco and shopped at the small boutiques. Catalina and I drove past the Hakims’ address, doubled back around the block, and pulled into a wide gated driveway. Three security guards looked at us and nodded. Catalina gave our names to one of them and he called upstairs. The gate opened and the guard motioned for us to drive through. Another guard met us in the visitor’s area where Catalina parked her car. We grabbed our bags and followed him to a stainless steel elevator. Inside, we smiled in anticipation. Salomon Hakim is a living national treasure whom Catalina, a native Colombian, knows through her studies, but has never met. She, herself, now a doctor, relished the chance to meet her country’s most beloved neurosurgeon. I felt much the same excitement. After months of researching and reading many of Hakim’s papers — including his initial thesis about NPH in 1964 — I only hoped not to make a fool of myself when we were finally face to face.

The elevator doors opened directly into the foyer of Fernando Hakim’s residence where a friendly, middle-aged housekeeper, wearing a crisp white smock, greeted us. Four families of the Hakim clan lived in the building. They each occupied separate floors where they could live their lives apart from one another but still be close. I remembered thinking that I wished I had this same arrangement with my parents. After a few minutes Fernando appeared and led us to a beautiful room decorated with artifacts from trips abroad and dolls ornately dressed in Harlequin costumes. “My wife likes those.” He said that his father lived on an upstairs floor and that he would soon take us to see him. “Would you like something to drink?” The housekeeper brought us each clear glasses of water. Fernando called his three very beautiful teen-aged children into the study to meet us —19-year-old Yvette, 17-year-old Denise, and 16-year-old Salomon. The boy wasn’t sure if he would continue the family tradition and enter the field of neurology but he still had plenty of time to decide. Fernando and I discussed what I needed for my research and he generously offered to give me photos and documents. He also warned that his father was not the same man today who had written the academic papers I read.

“He is only two percent of that man,” Fernando told me. He said that his father might not be able to remember all the details from past cases that I wanted to ask him about. I assured him that I understood. Fernando got up from his chair and motioned for us to come with him. We followed him through a side door, and up several flights of stairs.

Salomon Hakim at his home in Bogota, Colombia, during my visit | ©Rose Tibayan

Salomon Hakim was sitting quietly in a beautiful wooden chair beside a window when I met him. He wore a soft gray sweater and khaki pants. His study was decorated with volumes of favorite books, family photographs, and small gifts that had been given to him over the years. He smiled as we were introduced. As we were getting acquainted, Yvette Daccach came out to say hello. Hakim’s wife wore a boucle tailored jacket with pants and a perfectly coiffed head of silver hair. She looked distinguished and elegant. “Can we bring you something to drink?” she asked softly. She waited until the housekeeper brought some glasses then disappeared into another room.

Hakim was now eighty-eight years old. In his kind and sparkling eyes I could see the brilliant doctor and inventor who dedicated his life’s work to giving back lost years to elderly people. Hakim’s efforts had netted him worldwide recognition, accolades, dozens of patents and a comfortable lifestyle. But, even now, as he explained to us the

importance of his work, it was evident that his desire to bring people out of dementia’s darkness and oblivion was what truly drove him. He told me that the most important part of being a good doctor was to make a correct diagnosis. Hakim’s native tongue was Spanish but he accommodated me in English.

Two doctors. Salomon Hakim and Catalina | ©Rose Tibayan

“A person, or patient, with these symptoms, most of the people think that they have a bad disease — something that cannot be improved. You think for a moment… those cases can be improved 100%,” he said with emphasis by pointing a finger upward. “It’s worth it to know the diagnosis and to know how to make the diagnosis.” He patiently took some time to go through my list of questions. Often, Hakim couldn’t hear what I was saying so Fernando would repeat the question to his father by speaking inches from his ear. I asked him what he would most like people to remember about his work. “I would like that this normal pressure hydrocephalus, as it is called, will be known in the whole world as another contribution to medicine,” Hakim told me. “Because there are many patients, they cannot walk. Alzheimer’s doesn’t have any treatment. A person with true Alzheimer’s is lost while normal pressure hydrocephalus has many ways to treat it. One very simple way is through the implant of a valve. With this, a patient recuperates everything, 100%. So we have many cases like that.” After a while he seemed to tire and we knew that it was time to go. We said goodbye. When we left Hakim was reading a book about Isaac Newton.

****

Harold Conn eventually did get that scooter that his colleague in New Haven had denied him. But he never used it. The red-and-black “monument,” as he calls it, now sits in his living room foyer as a reminder of the hell he needlessly endured during the years of his misdiagnosis. After the miraculous results of his spinal tap in the neurologist’s office in Miami, Harold underwent a successful shunt implant. Afterwards, he couldn’t believe how much one operation had changed his life. It intrigued him that this cure had been available for decades, yet no one knew much about it. He decided to put aside his ongoing research about hepatology — his own medical field of expertise — and dedicated himself to the study of this “old-but-new” disease of NPH. He eagerly consumed information about the disease — clinical studies, history, and people associated with NPH.

“One of the things that attracted me to it was, whenever I asked anyone about it, they didn’t know what I was talking about.” NPH is an orphan disease. “As you know, I knew nothing about NPH until the day it was diagnosed in me and that was the first I had ever heard about it,” Harold told me when I visited him in his home in Florida. “And I was intrigued by this disease. Here was a disease that was lethal if left untreated… reversible, if treated… and treatment was relatively easy, surprisingly so.” He and Marilyn had resumed traveling again. “And the whole thing was like a dream.”

Harold had heard about the doctor from Colombia who had discovered NPH. He decided that he needed to meet him. “So I wrote a letter to Salomon Hakim. It wasn’t initially responded to,” he told me. “There was a delay of well over a month and then I got a telephone call.” It was Carlos, Hakim’s son. “My father has received your letter and is as interested in meeting you as you are in meeting him.”

THE DOCTORS MEET

The meeting between Salomon Hakim and Harold Conn happened in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, in December 2005. Marilyn remembers the first thing Hakim said to her. “What he said was, ‘I wanted to meet a doctor who had my disease.’ He called it ‘his’ disease. And he was very excited to meet Hal because they could talk at a level that most patients can’t [with their doctors].” She and Harold learned much about NPH that day. Hakim told them about how patients who successfully underwent a shunt operation not only lost the triad of NPH symptoms but were also, in a way, transported back in time. “He told us, and he was very excited about it,” said Marilyn, “that when someone has the surgery and whatever happens within the brain, everything is back to where it was, and that was just marvelous. I mean it was true with Hal and we had seen this.” The doctors talked for hours. “And it was fun,” said Marilyn. “It went on for about three hours in the lobby. It was all NPH. He was talking about some of his patients, I remember, and I was fascinated and he was describing how people would come in much worse off than Hal and they would do the surgery and they would… they would come alive again! It’s just an amazing thing.” Harold said there was no question that this wouldn’t be their last meeting. And it wasn’t. The Hakims and the Conns continued to remain friends and see one another over the years.

MANY ARE MISDIAGNOSED

Since Salomon Hakim first published his theory about NPH in 1964, there has never been a prospective epidemiologic study to establish the prevalence of the disease. What is known is based upon available data, which isn’t much. Doctors who treat NPH at the Chicago Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroresearch believe that only one in five people with NPH are properly diagnosed and treated. Doctors say that as our population gets older, however, the prevalence of NPH will increase.

Currently, NPH is considered an orphan disease, meaning that it affects fewer than 200,000 people. Pharmaceutical companies often give low priority to finding a cure for orphan diseases because their minimum prevalence provides little financial incentive for companies to research, manufacture, and market treatments and cures. In 1983, the US Orphan Drug Act gave tax incentives to clinical trials and seven years of exclusivity marketing for drugs developed for rare illnesses. Since that time the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 200 orphan drugs, which remain on the market. Other countries, such as Japan and Australia have adopted similar laws. As more and more doctors learn about NPH and learn to spot its triad of symptoms, we will most likely see numbers increase as newer diagnostic methods are developed. Those without access to regular medical care, let alone neurology specialists, have a greater chance of remaining undiagnosed.

Harold has been conducting his own NPH research. Currently, he has over a hundred cases collected from people who reach out to him. More than likely, most found Harold from reading his research papers, listening to an interview on the radio, watching his videos on YouTube, or seeing him seeing him on a local TV news show. “I’ve purposely done this because I think it’s important to get NPH exposed to the public.” In one of his studies he surveyed doctors for two years to see what percentage of them knew about NPH and, if they knew about it, what exactly did they know? “I made up a 10-question questionnaire and carried them with me. I mailed them to everyone on our list so I knew that we’d get the old people but we had 500 cards going out and about 150 people responded.” After calculating the results he was surprised to find that a large percentage of the doctors had never heard of NPH. “Fully a third are unaware of the existence of the disease and these are practicing physicians.”

Today, there are doctors who still don’t believe that NPH exists.

“I would say that there are perhaps two reasons,” says Carlos Hakim. “One of the reasons has been that many people have not accepted that the ventricles can increase in size with normal pressure. That, for many people, seems to be something that doesn’t make sense. Hakim told Carlos there had been an increase in shunt implants by doctors who hadn’t diagnosed the patient properly.

“When my father first described NPH in 1964 there was a lot of enthusiasm but the people went overboard shunting a lot of people who were really not candidates, who really did not have NPH with not good results. And so this diminished the interest of a lot of people.”

“I think they haven’t studied the syndrome,” says Fernando Hakim. “They don’t know about it. If you don’t know about something how can you believe in it?”

More recently, in the 1990s, there was incredible negativity about NPH to the point where some very respectable people in the field refused to believe that NPH exists. “I think like everything in medicine, there’s a certain art to the diagnosis and treatment,” says Relkin of Weill Cornell Medical School. “And people became frustrated over time because so many people come to the attention of neurologists because they have been found to have large ventricles in a scan.” Relkin says that few of the people tagged to have NPH actually have it. “So, on the radar screen of neurologists, eventually, you start to say this is a vanishingly small or non-entity.” But Relkin points out that there are also many successful cases in the treatment of NPH. “My experience and that of the colleagues that I work with internationally who have specialty centers who focus on this is very, very different. Very high success rate and, increasingly, low morbidity rate. So I do think that the field is changing, it’s evolving. I think we still have a long way to go.”

Harold doesn’t blame the colleagues from Yale who misdiagnosed him. “I had graduated from medical school in 1950 and the disease NPH had not been described until 1964,” he said. “So there was no way for me or any of my colleagues of same age or experience to be aware of the disease, so nobody saw it. And, my overall thought is that it probably takes thirty to forty years for an uncommon, new disease to take its place in medicine and be recognized by most practitioners. Not everybody knows everything.”

In January 17, 2000 the Virginia General Assembly placed NPH front and center by passing House Joint Resolution No. 45 requesting an epidemiologic study of the elderly population in Virginia’s long-term care facilities. They wanted to identify the number of patients suspected with NPH. The patrons of the study included Delegate Frank Hargrove, Sr. (R) of Hanover, whose wife Oriana, was diagnosed with NPH after a decade of being misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s. She was recovering in a hospital after a bad seizure when a nurse, who noticed her symptoms, suggested that she might have NPH. Anthony Marmarou, the doctor who successfully treated Oriana Hanover with a shunt, estimated that NPH affects up to one in ten of the 7.5 million Americans currently diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. He believes that one in seven people in assisted-living facilities and nursing homes have NPH.

Like the Virginia effort to determine the prevalence of NPH cases in local nursing homes, there were many other small, independent ongoing studies around the world. Yet, there was still no accepted diagnostic procedure for NPH, and no definition that clinicians around the world could use when doing their own study. “There was no agreement in the clinic what constituted a patient who had NPH or how you should come to the conclusion when you had a patient and you suspect they had it,” said Relkin.

That all changed in 2005, when Relkin and a group of neurologists got together to create NPH standards and guidelines. Up until that point, no one had agreed upon guidelines for diagnosing NPH so it was impossible for researchers to compare studies with one another. “They mixed together patients with primary, or secondary, or idiopathic forms of hydrocephalus,” said Relkin. “How could we create an infrastructure going forward for unified types of clinical studies where everybody had their oars in the water and were rowing in the same direction?” Dr. Jose Espinosa, a neurosurgeon at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine said that any guidelines created should not only make it easy for doctors to treat patients, but should convince public and private insurance companies to pay for up to three days of tests in the hospital. "We need a better way to find out who has it and who doesn't," he said.

The organized effort has resulted in progress. Today, between 300 to 400 people internationally are actively working on NPH as their primary focus. And, since guidelines were published in 2005, about 50 papers have emerged which have used the guidelines for their studies. “I think third-party payers have paid attention to it, shunt manufacturers have paid attention to it,” said Relkin. “A third party payer can go to that neurologist or neurosurgeon opinion leader

and say, does this entity exist? Should I pay for it? They can’t say no, there’s no such thing as NPH because now there’s a body of evidence and expert opinion that points otherwise.”

In addition there are new technologies, or enhanced previous technologies, which have been developed specifically for the diagnosis of NPH. These include Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Phase Contrast MRI (PC-MRI), Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), MRI volumetry (V-MRI), Magnetic Resonance Intracranial Pressure measurement (MR-ICP), Arterial Spin Labelling (ASL), and CSF Proteomics. “In my own personal experience I feel that we’ve turned the corner in terms of having other modalities that we never had before, that give us a much clearer picture on what we’re seeing. So, I don’t feel my hands perspiring when I’m encountering a patient with suspected NPH anymore because I know where to go. I know what to do and in most cases I get a very, very clear answer.”

FINAL STEPS

Harold Conn is now 86 years old. He continues his NPH research to help others but is being vigilant about what is happening to his own situation. As he gets older, he has felt his body regressing into the abyss of symptoms that he had overcome with the implanting of his shunt. “He had about seven good years,” Marilyn told me. Not everyone who managed to recover from NPH slips backwards. There are countless stories of patients whose shunts were planted more than 20 years ago and are still as healthy as ever, today. Had Harold been diagnosed earlier, his story could be different today.

Salomon Hakim is now 88 years old. Although his memories are slowly diminishing, he lives surrounded by countrymen who respect him and family members who love him. His efforts have finally been recognized by his colleagues at MGH. On the hospital’s Internet page of notable neurosurgical alumni, Hakim has been given a place among the most important contributors as the founder of “this clinical entity known worldwide as the Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, NPH or Hakim Syndrome.” Inside, his name appears, once more, along with two of the original five authors of the controversial 1965 article printed in the New England Journal of Medicine. “In association with Professors Robert Ojemann and C. Miller Fisher, Dr. Hakim defined the clinical syndrome Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus or Hakim's Disease during his fellowship at MGH. He has continued to study CSF physiology and to contribute to the treatment of hydrocephalus with developments such as the Hakim shunt valve.”

“He was the one who really opened the eyes to one of the really treatable types of dementias,” said Carlos Hakim. “Because many years ago you would speak about the word dementia and treatable — those two things did not go together. He was the first one who really started studying the brain from a physical, or hydraulic point of view. And I think that opened the eyes to everything that’s happening now.”

“He is a person that has helped so many persons around the world,” said Fernando Hakim. “If he could stop for a minute and think, ‘how many people have I helped, how many people could have been dead, how much quality of life did I improve, how many lives did I save with this shunt that I invented? I think there’s many people that have been favored with what my father did, or has done.” Salomon Hakim knows what he has done. He is happy that he was able to do it. “Always you do something but you can think you can do better. So I think that I did my best and I think I’m happy for this.”

My father, whose tell-tale gait had finally been recognized after all those years, went on to receive a spinal tap. I was there and saw the successful result. Like Harold Conn, he miraculously got up off the table, walked right past his wheelchair, and began speaking clearer than he ever had before. The only step left was the shunt operation. Unfortunately, my father ran out of time.

Manuel Tibayan died of a brain aneurism on August 30, 2010 — one day before he was to meet the neurosurgeon who would have implanted his shunt. His story, unfortunately, is a common one among those robbed of precious time because of a misdiagnosis. My father was 80. Had I known about NPH much earlier, perhaps I would have been able to make a difference in helping to save my father and extend his life — perhaps making his final years happier, more productive, and with more dignity. Even though he didn’t make it in time for my walk down the aisle on my wedding day to begin my new life, I was there for him as he took his final steps of his life. ✿

[MY NOTE: Five months after I interviewed Dr. Salomon Hakim in 2010, he passed away. Dr. Harold Conn died the following year.]